2025 Nobel Prize in Economics: Innovation, Creative Destruction, and Sustainable Growth — and What It Means for Germany

TL;DR: The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics honors Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt for explaining how innovation drives sustained growth. Mokyr identifies the historical preconditions that allow innovation to accumulate; Aghion and Howitt formalize how creative destruction underpins modern growth. Together, their work clarifies why growth cannot be taken for granted—and what kinds of policies Germany now needs to secure its economic future.

Introduction

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences was awarded jointly to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt for their fundamental work on innovation-driven growth.

Mokyr’s historical analysis explains why sustained growth emerged only under specific institutional and cultural conditions, while Aghion and Howitt’s theoretical model shows how innovation endogenously fuels growth through the process of creative destruction.

Together, their work provides a unified narrative: innovation is the engine of prosperity, but its power depends critically on the societal and institutional environment that allows new ideas to flourish and old ones to fade.

Recent News that complement this narrative

Some recent news that appeared after this post was written but are relevant to the discussion:

- The Economist: How Europe crushes innovation

- A European attempt to catch up: EuroLLM

Mokyr: The Preconditions for Sustained Growth

Joel Mokyr’s research asks a deceptively simple question: Why did the Industrial Revolution happen when and where it did? His answer lies not in the invention of particular machines, but in the emergence of an environment that made continuous innovation possible.

For much of human history, inventions appeared sporadically but failed to trigger self-sustaining growth. Mokyr identifies three essential conditions that finally broke that pattern.

1. Science and Technology Co-Evolving. Growth accelerated when scientific understanding and practical engineering began to reinforce one another. The interplay between theory and application—seen in mechanics, thermodynamics, and chemistry—created a virtuous cycle of cumulative improvement.

2. Engineering Capability and Mechanic Competence. Scientific knowledge alone was not enough. Societies also needed the ability to implement ideas at scale: skilled artisans, standardized components, effective apprenticeship systems, and eventually formal engineering education. This infrastructure enabled the transformation of insight into industrial capability.

3. Openness to Disruption. Perhaps the most fragile condition was social and institutional openness to change. Continuous innovation means continuous displacement—of technologies, firms, and sometimes entire industries. Where vested interests could block such shifts, growth remained episodic.

Implications

Mokyr’s message is timeless: innovation without diffusion, engineering capacity, or openness cannot sustain prosperity. Even advanced economies risk stagnation if they lose these enablers—whether through regulatory rigidity, skill erosion, or entrenched incumbency.

Aghion-Howitt: Creative Destruction

Aghion and Howitt revolutionized growth theory by bringing innovation inside the model. Instead of treating technological progress as an external force, they described it as a product of firms’ strategic choices—to invest, to compete, and to risk being replaced.

Their framework captures the Schumpeterian idea of creative destruction: progress occurs because new technologies displace old ones. This destruction is not a side effect: it is the very mechanism that keeps growth alive.

The Core Mechanisms

1. Endogenous Innovation: Firms innovate when they expect profits from doing so. R&D intensity depends on incentives, policy, and market structure.

2. Competition and the Inverted-U: Innovation is most vibrant under moderate competition—too little protects monopolists; too much erodes potential gains.

3. Entry, Exit, and Reallocation: Dynamic economies rely on turnover. New entrants challenge incumbents, and resources shift toward more productive uses.

Through this lens, growth becomes a process of continuous experimentation, selection, and renewal.

Policy Lessons

Aghion and Howitt’s theory highlights the interdependence of R&D policy, competition policy, and education/labor systems. Each shapes the incentives that determine whether an economy encourages the next generation of innovators; or protects the last.

Innovation, Growth, and Sustainability

Innovation is the only long-run source of growth. But innovation alone does not guarantee it. The engine must run within a system that supports both discovery and renewal. In Mokyr’s terms, science, technology, and social openness must align. In Aghion–Howitt’s framework, competition and institutional design must sustain incentives for continuous creative destruction. Sustainable prosperity, then, is less about preserving existing strengths than about preserving the capacity for renewal—the ability to replace outdated ideas, technologies, and firms with better ones.

What this says about innovation in Germany

Even before the 2025 Nobel announcement, leading growth economists such as Philippe Aghion had warned that Europe, and Germany in particular, no longer fully satisfies the institutional and cultural conditions for innovation-driven growth. Aghion, Dewatripont, and Tirole argue that since the 1990s, Europe has failed to establish the environment required for disruptive innovation: a fragmented single market, underdeveloped venture-finance and risk-capital systems, and a policy culture favoring stability over experimentation. As a result, Europe risks becoming trapped in what they call a “middle-technology equilibrium”, strong in incremental improvements but weak in frontier innovation and technological leadership. These critiques directly echo the Nobel laureates’ insights: innovation must operate within an institutional system that tolerates creative destruction and rewards renewal rather than preservation.

Germany’s economic strength has long rested on engineering excellence, industrial depth, and institutional reliability. These pillars have produced remarkable prosperity through incremental innovation and quality leadership. Yet, as the recent Nobel Prize in Economics underscores, sustained growth in the twenty-first century depends increasingly on creative destruction — the continuous renewal of technologies, firms, and ideas through innovation.

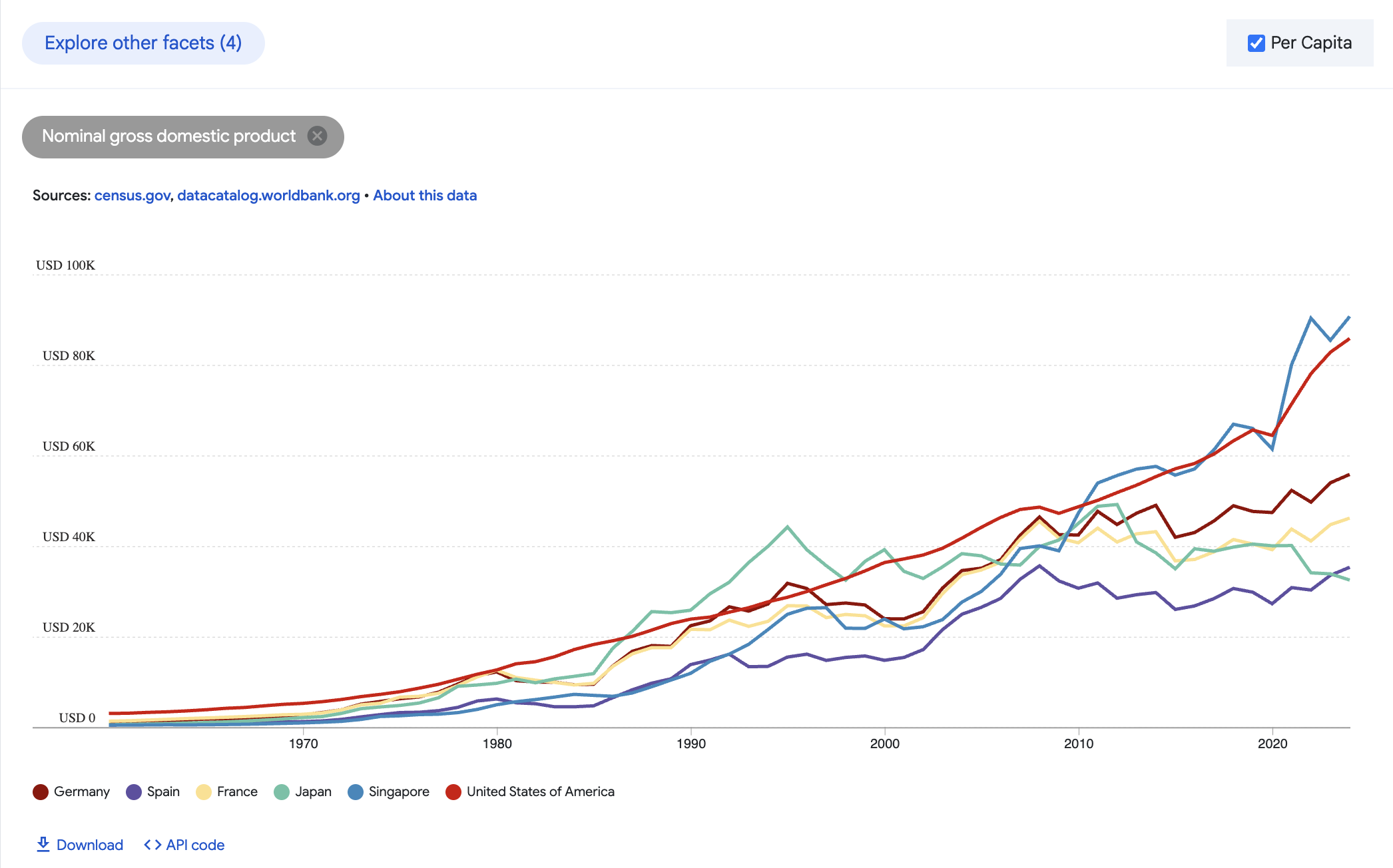

To maintain global competitiveness and resilience, Germany must complement its traditional stability-oriented model with greater openness to disruption, faster diffusion of frontier knowledge, and stronger incentives for entrepreneurial risk-taking. This is not only an economic imperative but a demographic one: with an aging population and a steadily declining workforce, productivity growth is essential to counteract demographic headwinds. Since the end of the 2000s, Germany’s GDP per capita has remained largely flat, signaling that without renewed innovation dynamics, overall prosperity will not only stagnate but sharply decline.

As such a more agile regulation, a dynamic venture landscape, and a culture that sees change not as a threat but as the very source of sustainable prosperity is needed. Strengthening the interface between research institutions and the broader innovation ecosystem can play a decisive role in this transition.

Figure 1: Nominal GDP per capita (via datacommons.org).

The Historical Layer: From Stability to Dynamism

Postwar Germany built its prosperity on incremental innovation and stability. The country perfected the art of refining existing technologies rather than replacing them. This model—anchored in engineering excellence, vocational training, and social partnership—created high productivity and resilience but limited tolerance for disruption.

In Mokyr’s terms, Germany excels in mechanical competence but underinvests in openness to disruptive change. Institutions, regulations, and social norms that once guaranteed continuity now risk locking the system into the past.

Key Tension: Germany’s model maximized stability and diffusion, not frontier innovation. The very strengths that drove its success is now slowing down innovation and adaptation.

The Structural Layer: Inertia vs. Innovation Dynamics

Aghion & Howitt’s growth framework emphasizes continuous entry of new innovators and exit of outdated firms. Germany’s industrial ecosystem, however, tends to favor incumbents and gradualism.

| Mechanism (Aghion–Howitt) | Tendency in Germany | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Entry of new, innovative firms | Low startup rate, complex regulation, conservative finance | Slower technological frontier shift |

| Exit of outdated firms | Social and political resistance (e.g. subsidies, bailouts) | Delayed reallocation of resources |

| Competition intensity | Often moderate-to-low in core sectors (automotive, energy, finance) | Weaker innovation pressure |

| R&D structure | Strong in applied engineering, weaker in digital and AI | Imbalance in innovation types |

| Labor mobility | Low due to firm loyalty and vocational specialization | Slow diffusion of new ideas |

This structure is highly optimized for incremental improvement: excellent at perfecting combustion engines or machine tools, but less agile when the frontier shifts toward AI, software, and renewable systems.

In short: Germany is a world leader in innovation within existing paradigms, but struggles to innovate across them.

The Policy Layer: Institutions and Incentives

The policy environment reflects the same equilibrium: one optimized for stability and incremental improvement rather than experimentation and renewal.

- Finance: Germany’s bank-centered system channels capital primarily to established firms with tangible assets and proven track records. Venture and growth finance remain limited in volume and depth compared to the U.S. or China, constraining the scale-up of young innovative firms. Public financing instruments, though substantial, often emphasize risk minimization and compliance over agility and experimentation.

- Regulation: Complex approval procedures, fragmented jurisdictions, and slow digital administration increase transaction costs and delay the deployment of new technologies. Even pilot projects or regulatory sandboxes face multi-year approval timelines, reducing the incentive for entrepreneurial experimentation.

- Public R&D: Institutional research networks such as Fraunhofer, Helmholtz, and Max Planck as well as excellent universities deliver outstanding science and applied engineering, but translation into scalable high-growth enterprises remains the weak link. Structural barriers between academia and entrepreneurship, ranging from intellectual-property rules to career incentives, limit the spillover of frontier research into the private sector.

- Competition Policy: Designed to safeguard fairness and prevent monopolies, it sometimes has the side effect of preserving incumbents. High regulatory thresholds and sectoral protection dilute entry pressure and reduce the dynamism of domestic markets, particularly in energy, finance, and telecommunications.

These features supported stability, quality, and long-term employment for decades. Yet today they constrain dynamism, speed, and adaptability—precisely the qualities that define success in innovation-driven economies. In Aghion’s terms, the current policy mix underweights entry dynamism: the continual churning of firms that fuels creative destruction and renewal. Sustained growth, however, requires institutional agility: policies that reward experimentation, accept short-term disruption, and tolerate failure as part of the innovation process.

Why It Becomes a Problem

The laureates’ work helps explain why Germany’s model now faces mounting structural headwinds. What once guaranteed stability and prosperity now risks impeding adaptation to a faster, more fluid global innovation landscape.

- Acceleration of technological cycles: Innovation now unfolds at software speed, while Germany’s institutions and industrial processes still move at mechanical speed. The product cycles of AI, digital platforms, and biotech evolve in months, not decades, demanding a pace of response the traditional system struggles to match.

- Shift from physical to digital: Value creation increasingly depends on algorithms, data, and networks rather than production volume or material precision. Germany’s comparative advantage in manufacturing excellence thus erodes unless accompanied by digital capability and data-driven innovation.

- Global competition for innovation: Ecosystems in the United States, China, and South Korea combine capital depth, entrepreneurial risk appetite, and scale in ways Europe and Germany have not replicated. These ecosystems attract top global talent and absorb frontier innovations faster, creating a widening gap in technological leadership.

- Over-embedded incumbency: Political, social, and financial systems continue to shield existing industries—automotive, energy, finance—from disruption. This “incumbent bias” prevents reallocation of capital and talent to emerging sectors and delays renewal.

- Hesitance to adopt external innovation: Beyond domestic inertia, Germany also tends to underutilize external technological breakthroughs. Imported digital and AI tools are often viewed through a compliance or risk lens rather than as catalysts for reinvention. This reluctance to integrate global frontier technologies into local production chains further widens the innovation gap.

The result is a growing mismatch between the velocity of global technological change and the institutional response capacity of Germany’s economic model. Without structural renewal, the innovation–growth link weakens, turning creative destruction into mere creative delay.

In Aghion’s terms, Germany risks falling into a middle-technology equilibrium: a state of high competence in established industries coexisting with stagnation at the technological frontier. In the face of demographic decline and a shrinking labor force, productivity growth through innovation is no longer optional; it is the only path to sustaining prosperity.

Institutional agility, policy experimentation, and a proactive innovation agenda are therefore not economic luxuries but existential necessities. Or put it in the famous words attributed to W. Edwards Deming:

“It is not necessary to change. Survival is not mandatory.” — W. Edwards Deming

What Compatibility Would Require

To realign with an innovation-driven growth path, Germany must evolve from a stability model to a renewal model. One that sustains its strengths while restoring openness, experimentation, and competition.

- Cultural Shift: Move from risk avoidance to curiosity and experimentation.

- Dynamic Competition: Strengthen antitrust tools, encourage market entry, and curb excessive concentration.

- Faster Diffusion: Create translational institutions between academia and startups; reduce administrative friction.

- Deep Capital Markets: Expand venture and scale-up finance; modernize taxation of employee equity.

- Talent and Skills Renewal: Extend the dual education model to digital, AI, and systems engineering; simplify international recruitment.

- State as Catalyst: Use public procurement and infrastructure investment to create domestic lead markets for innovative solutions.

- Institutional Agility: Embed experimentation into policy, via sandboxes, adaptive regulation, and outcome-based funding.

Sustainable prosperity is no longer about preserving existing strengths, but about preserving the capacity for transformation.

Afterword

Several years ago, in February 2020, I was flying back to Germany from Atlanta and my flight was delayed and it became clear that the pilot won’t be able to make up the time. So I logged into the onboard wifi, opened my (then still) Twitter app and DMed the @Delta twitter account as I had done numerous times before. No 10 minutes later I had my connecting flight rebooked; even though the connection was on a non-SkyTeam carrier. No hassle, no waiting in line, no waiting in line again. It. Just. Worked.

Figure 2: Innovation in action: Delta flight rebooking midair in 8 minutes.

References

- Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences 2025 — Press release https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2025/press-release/

- Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences 2025 — Popular information https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2025/popular-information/

- Reuters — “Trio win Nobel economics prize for work on innovation, growth and creative destruction” https://www.reuters.com/world/mokyr-aghion-howitt-win-2025-nobel-economics-prize-2025-10-13/

- The Guardian — “Nobel economics prize: technology-driven growth (Mokyr, Aghion, Howitt)” https://www.theguardian.com/business/2025/oct/13/nobel-economics-prize-technology-joel-mokyr-philippe-aghion-peter-howitt

- Financial Times coverage https://www.ft.com/content/9b845160-f44b-4865-94f7-1bf21e25596e

- Le Monde (English) — Philippe Aghion: “The key factor of economic power is technological leadership” https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2025/10/13/2025-nobel-winner-philippe-aghion-the-key-factor-of-economic-power-is-technological-leadership_6746390_4.html

- Philippe Aghion, Mathias Dewatripont & Jean Tirole (2024). “Can Europe Create an Innovation Economy?” Project Syndicate, October 2024. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/europe-falling-behind-us-innovation-technology-what-to-do-about-it-by-philippe-aghion-et-al-2024-10

- VoxEU/CEPR (2024). “Reforming Innovation Policy to Help the EU Escape the Middle-Technology Trap.” April 2024. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/reforming-innovation-policy-help-eu-escape-middle-technology-trap

- Financial Times (2025). “Economics Nobel Prize Awarded for Explaining Innovation-Driven Growth.” October 2025. https://www.ft.com/content/9b845160-f44b-4865-94f7-1bf21e25596e

Comments